How the POSITION of our HEAD and ANXIETY Responses mutually influence one another

Dec 20, 2022Abstract

Our loyal readers know we always check our theories, in order to verify their fundamentals and the effectiveness of some possible applications.

This article is about the results of a study that aims at verifying how mind and body mutually influence one another and general daily situations. This is a topic we regard as particularly important, being at the basis of the many techniques we use. Our objective is to be really sure about the precision of the mechanisms on which both the technique and its effectiveness are based and of their actual impact.

We evaluated if our emotional state can influence our posture in bed or when driving and if, on the other hand, such postures can influence our emotional responses.

The Basic Mechanism of the Shifting Movement of Our Head

The starting point is a very well-known and demonstrated phenomenon: states of fear, anxiety, stress and distress, change in our breathing which, as the result of a biomechanical phenomenon shown henceforward, shift the position of our head.

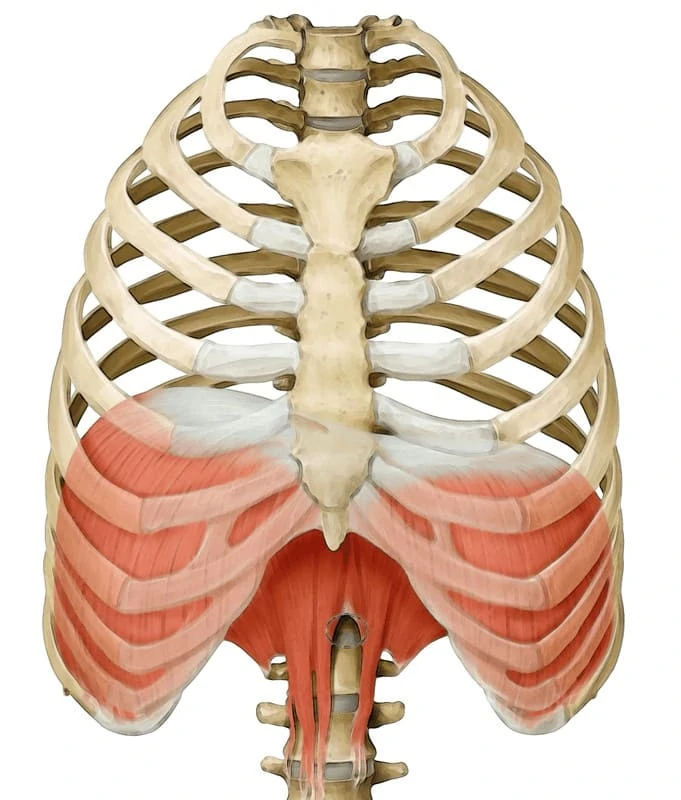

In order to better understand this phenomenon we must consider that our limbic system, when facing a danger, quickly activates (in milliseconds) a broader breathing. The goal is to bring more oxygen to our muscles, allowing them to fight or flee (it is a reflex we inherited from mammals.) To do this, diaphragmatic breathing (also known as “belly breathing,” as every breathing causes our digestive organs to move back and forth) increases, triggering thoracic breathing too.

Here come some complications.

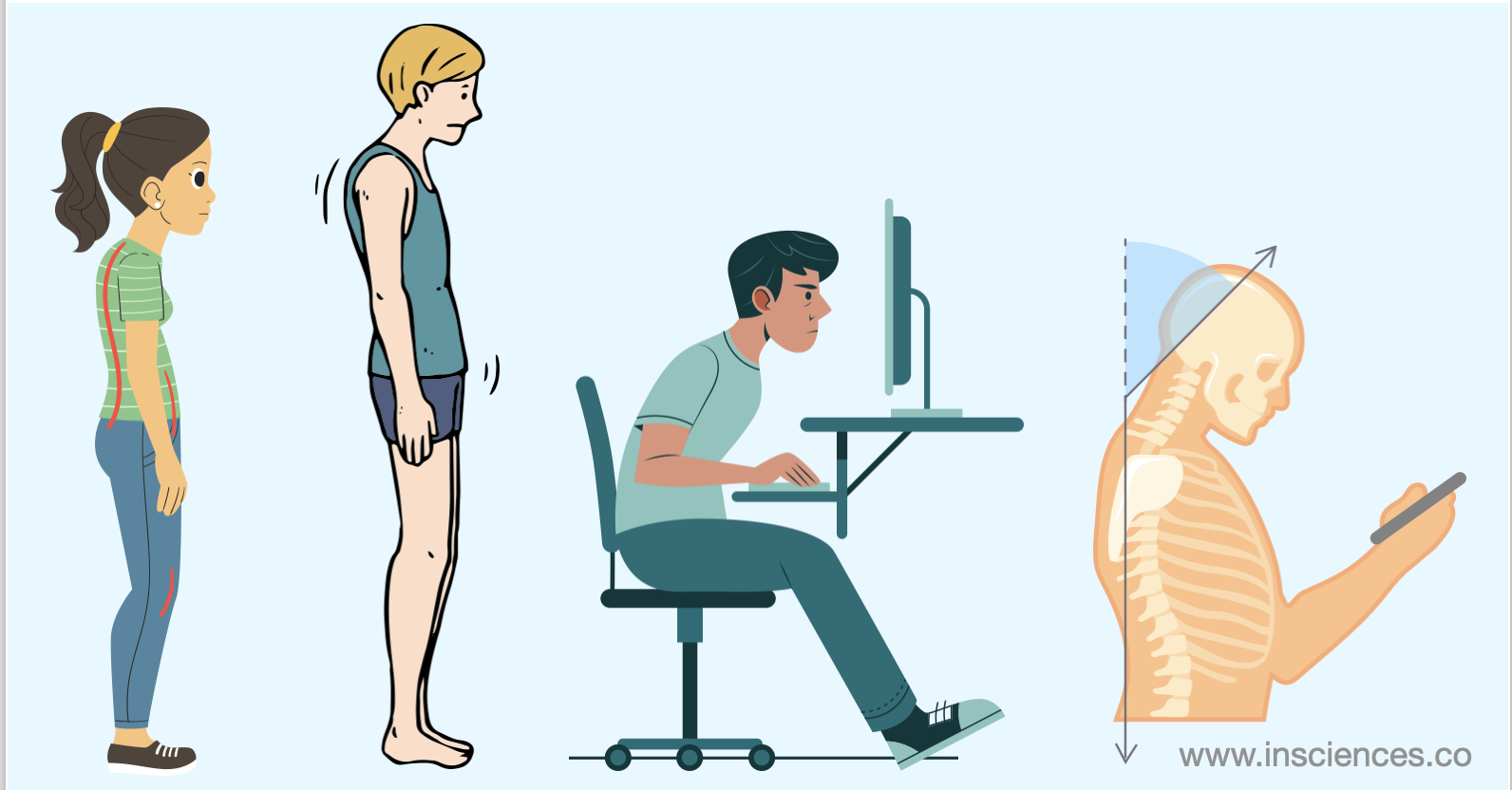

The first is about the fact that most people already use a thoracic breathing (which, physiologically, should not be used so much) and barely use the diaphragmatic breathing, if not at all. This happens mainly for cultural reasons: “Stomach In, Chest Out” seems to have become our leitmotiv from our early childhood.

This also happens with clothes (think of high heels for women) and, as a consequence of incorrect posture, when studying and working. Another cause for this non physiological breathing can be found in missed recovery times. Other mammals, that use the same breathing process we do, have time to rest after a stressful event, allowing their mind-body system to return to physiology.

Human beings, on the other hand, experience a stressful event after another, for instance in traffic, at a business meeting where we must present the results of our job and then facing a stressful call. Our body does not have enough recovery time. What happens is what we call an increase of threshold.

It is a complex phenomenon. Suffice to know our body stops feeling less intense signals of disturbance and distress, which create medium and long term problems. Such increase also happens if diaphragm, the basic muscle for a correct breathing, stiffens and shortens. This worsens our breathing and, for the peculiar shape of the muscle (of a bell) and its joints with the skeleton, increases our lordosis at both the cervical and lumbar level.

This mechanism makes us lift our head upwards, as if we were looking at something. But considering that most of the time we have to look at something straight ahead of us or downwards (other people’s faces, computer monitors, books, phones etc.) some of our muscles will push our head ahead instead of rotating it and bring it to the correct position.

That is the result of the position of our muscles and their strength. The effect looks like the neck and head of a turtle. Many other factors can contribute to this shift in the position of our head. The goal of this article is not to deepen this particular aspect; for now suffice to know that the mechanism we have just described has a strong impact on most people.

The experiment

The meaning of our experiment can now be fully comprehended, as we understood the mechanism linking the type of breathing we experience as we are afraid, are under stress, feel anxious and the forward movement of our head.

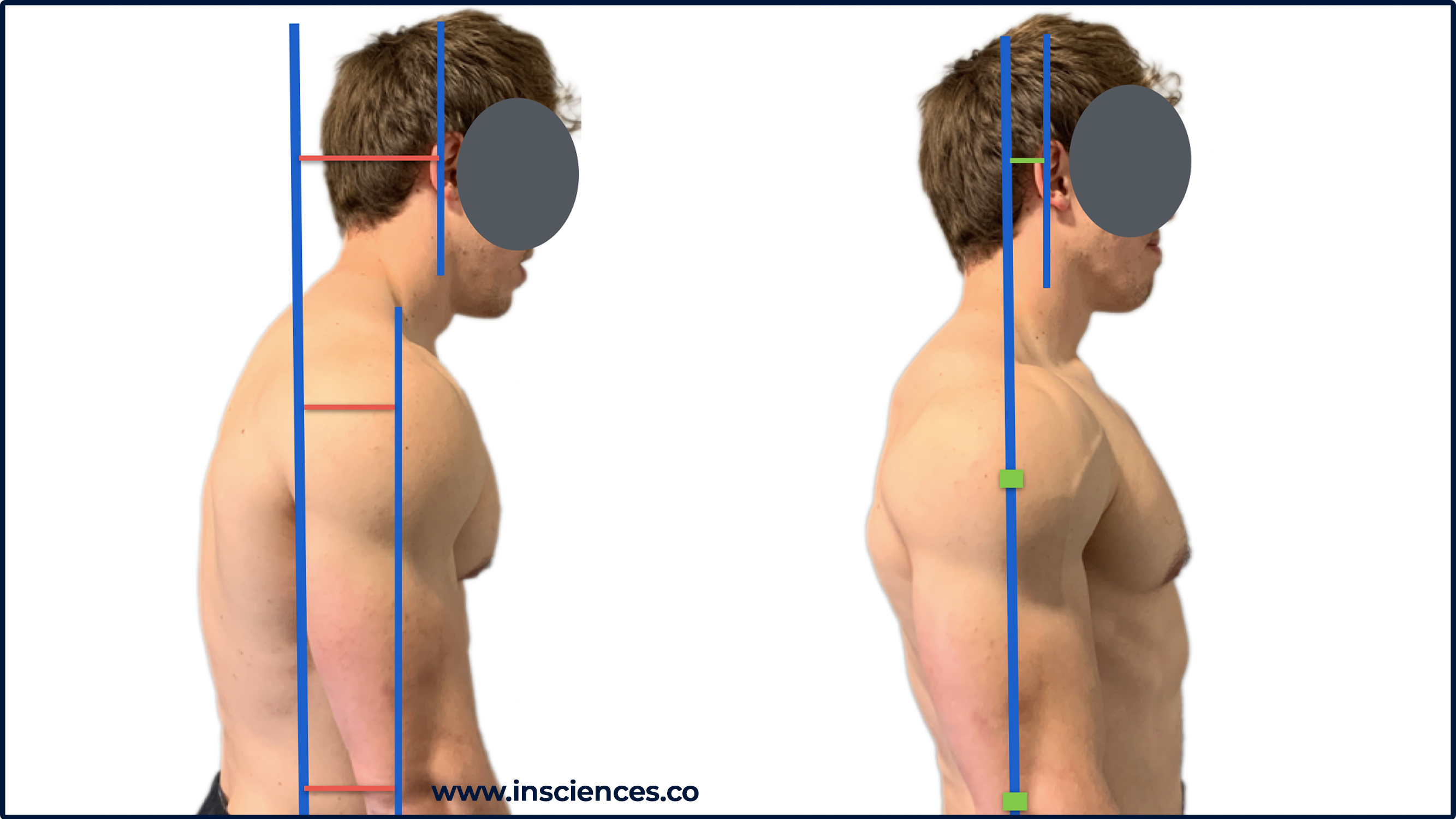

According to many physiological and anthropological approaches the sideways posture of a person in physiology provides that the nape (that is, the back of the head) must be aligned with shoulder blades and sacrum. This alignment can easily be verified in two typical daily occurrences: while lying in bed facing upward (on our back) and when we sit in our car. Of course, the mattress should be rigid enough and the seat must be placed in the correct position.

In our research, as Fabio Sinibaldi (one of the founders of Integrative Sciences; in charge of the applied research department) points out, we wanted to verify if working on emotions could influence our posture and also if emotional responses help restore more physiological conditions to our posture.

Do do this, we took three groups of people:

- The first group followed a basic emotional training (taken from the Switch Model, the Integrative Functional Patterns and the psychosomatic release technique Mouth, Anger and Stress) with exercises (Crossed Cycles Breathing, Reboot Techniques, and more) and practical instructions to apply for 15 minutes a day.

- The second group was trained about posture management with regard to emotions and directions on breathing (taken from another step of our Protocol) to be applied in a three-minute session for five times a day.

- The third group, the control group, did nothing.

- Training time was three weeks for each group.

At the beginning of the training, every new week and at the end o ever week, each group was monitored for the following aspects:

- Height of pillow for a comfortable position when lying on their back (every person was given 4 different pillows that respectively lifted them up 1, 2, 4, 6 cm. They were also free not to use any of them.)

- Seated in a comfortable position in the car, the distance between head and headrest, in centimetres.

- Heartbeat

- Salivary cortisol

- Degree of instant anxiety according to a self-report questionnaire

- Degree of basic anxiety according to a self-report questionnaire

Results

Group 1 – Emotional Training

- Average reduction of 2.8 cm in bed and 3.2 in the car

- Average reduction of 13% in heartbeat

- Average reduction of 19% in salivary cortisol

- Average reduction of 38% in the degree of perceived instant anxiety

- Average reduction of 57% in the degree of perceived basic anxiety

- Average reduction of 3.6 cm in bed and 4.8 in the car

- Average reduction of 19% in heartbeat

- Average reduction of 20% in salivary cortisol

- Average reduction of 31% in the degree of perceived instant anxiety

- Average reduction of 32% in the degree of perceived basic anxiety

Parameters showed no meaningful changes, only a slight decreasing tendency for all parameters (particularly an average reduction of 0.5 in the pillow) mainly due to a better self-perception, a self awareness brought by the involvement in the experiment.

Conclusions

This study confirmed both approaches: from emotions to body and, vice versa, from body to emotions. In particular, it is useful to observe that a coherence of action is found in both cases and with good results: the intervention on the body has a bigger effect on posture and heartbeat, whilst the one on emotions records a bigger effect on perceived wellbeing. Salivary cortisol is influenced in similar ways.

Another important aspect worth being valued is its efficacy related to the short duration of the training. In both cases, practice was required for 15 minutes a day for three weeks. Results were visible from the first week, but became meaningful at the third checking point. A follow-up after three months showed an average of maintained benefits between 60 and 85% of the results.

One last important aspect, which was not initially considered in this study but was reported by many participants, regards the self-perception of personal confidence in interpersonal relationships. In fact, if we take a careful look at the posture of very self confident people, their head is always well straight above their shoulders, while a head leaning forward is always a sign of uncertainty, as the above image clearly shows, perfectly aligned with the character played by Edward Norton in the motion picture Fight Club.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.